Efforts are under way to identify 27 people who drowned crossing the English Channel.

Their deaths have raised questions about why so many people are attempting the journey despite the dangerous conditions.

Why do migrants cross the Channel in boats?

For years, people smugglers have sent people to the UK in lorries. There have also been tragedies on these routes, including the 39 Vietnamese people found dead in a refrigerated lorry in 2019.

But security at the Port of Calais in France – where UK border controls are – has been tightened.

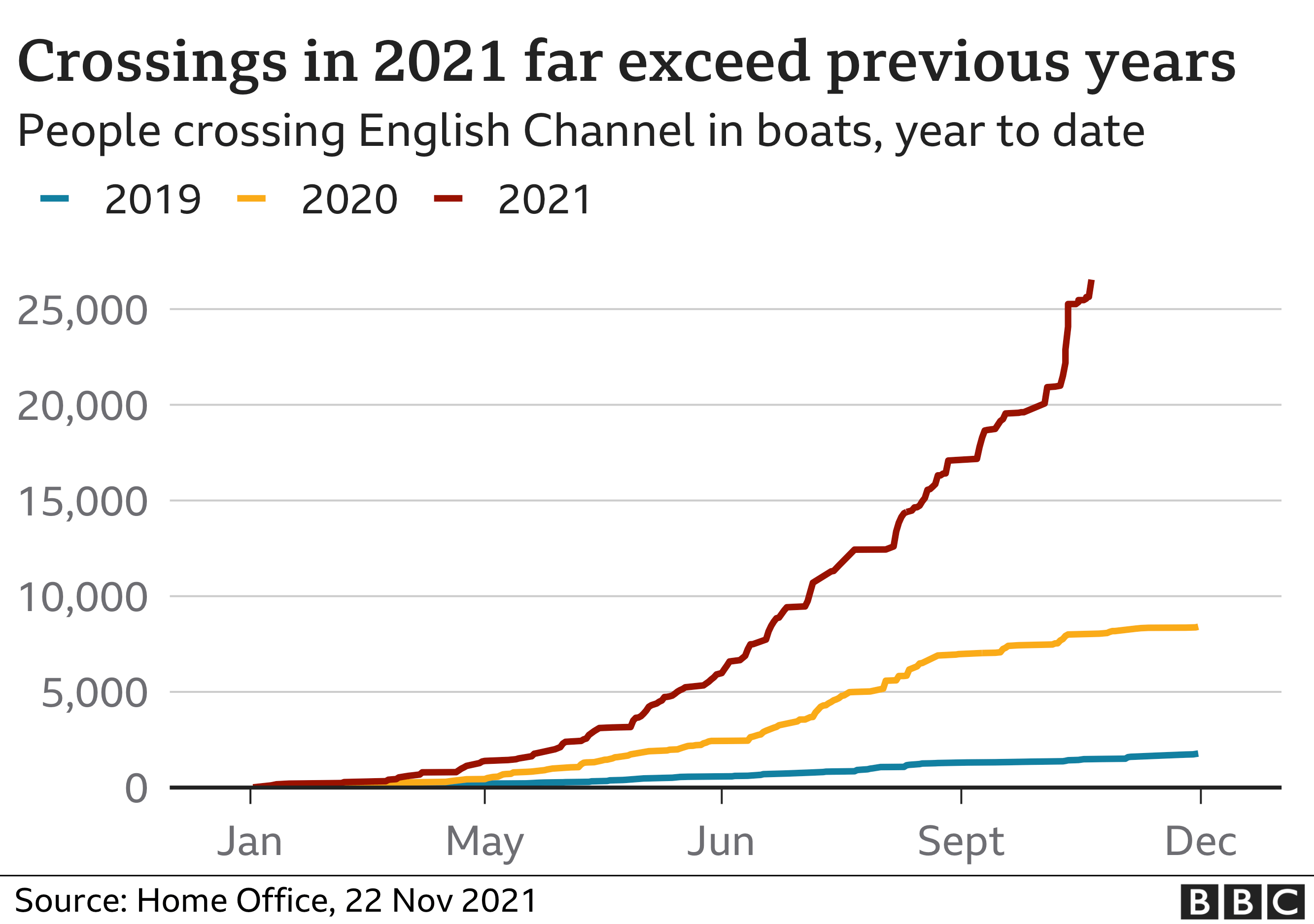

This means more attempts are being made to send people by boat, according to Tony Smith, former director general of UK Border Force.

He says Covid has also had a role, as fewer lorries have been travelling to the UK: “Human smugglers have changed their tactics and they’ve now taken to this relatively new phenomenon of putting people into small boats and bringing them across in that way.”

Why do migrants leave France for the UK?

In the few studies that exist, family ties have been identified as the main reason migrants wish to travel from France to the UK.

In a survey of 402 people at the former Calais “Jungle” camp, researchers from the International Health journal found only 12% wanted to remain in France, while 82% planned to go to England.

Of those that wanted to travel to England more than half (52%), said they already had a family member there.

“They have a connection to the UK, they speak some English, they have family, they have friends and people in their networks. They want to come and stay and rebuild their lives,” says Enver Solomon, chief executive of the Refugee Council.

Do migrants travel for jobs and money?

It has been suggested the UK’s jobs market often attracts migrants – a claim supported by the French Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin. There aren’t reliable surveys to support this though.

Marley Morris, an immigration expert at the IPPR think tank says the UK has introduced policies that make it much harder to work illegally.

“These arguments were put forward 20 years ago, when people said the UK system was too generous. The UK responded by tightening up the rules.

“While we don’t have ID cards, the policies introduced make it much harder to work illegally, [and] employers are fined for employing someone for not having the right to work.”

As well as language and family ties, some Calais-based migrants told the BBC they wanted to come to the UK due to historic links with their own country.

Some also expressed unhappiness at the way they are being treated in France, which can lead to more people attempting to make the crossing according to Rob McNeil, deputy director of the Migration Observatory at Oxford University.

“Imagine you are being poorly treated in the country you are in. Your presumption is that the immediate environment is unpleasant and you want to get away from that”, he says.

IMAGE SOURCE,PA MEDIA

IMAGE SOURCE,PA MEDIAIt’s unlikely that migrants choose to come to the UK because they feel they have less chance of being sent back compared to other European countries adds Mr McNeil.

“One thing we know is that the data suggests that people travelling to any country have very little knowledge of the laws and practices of enforcing immigration,” he says.

Despite the dangers, some say they have already taken significant risks to get as far as Calais and are willing to take further ones to get to the UK. For example, the International Health journal study also found that two-thirds of people had experienced at least one act of violence during their journey or in Calais.

How many migrants travel to the UK?

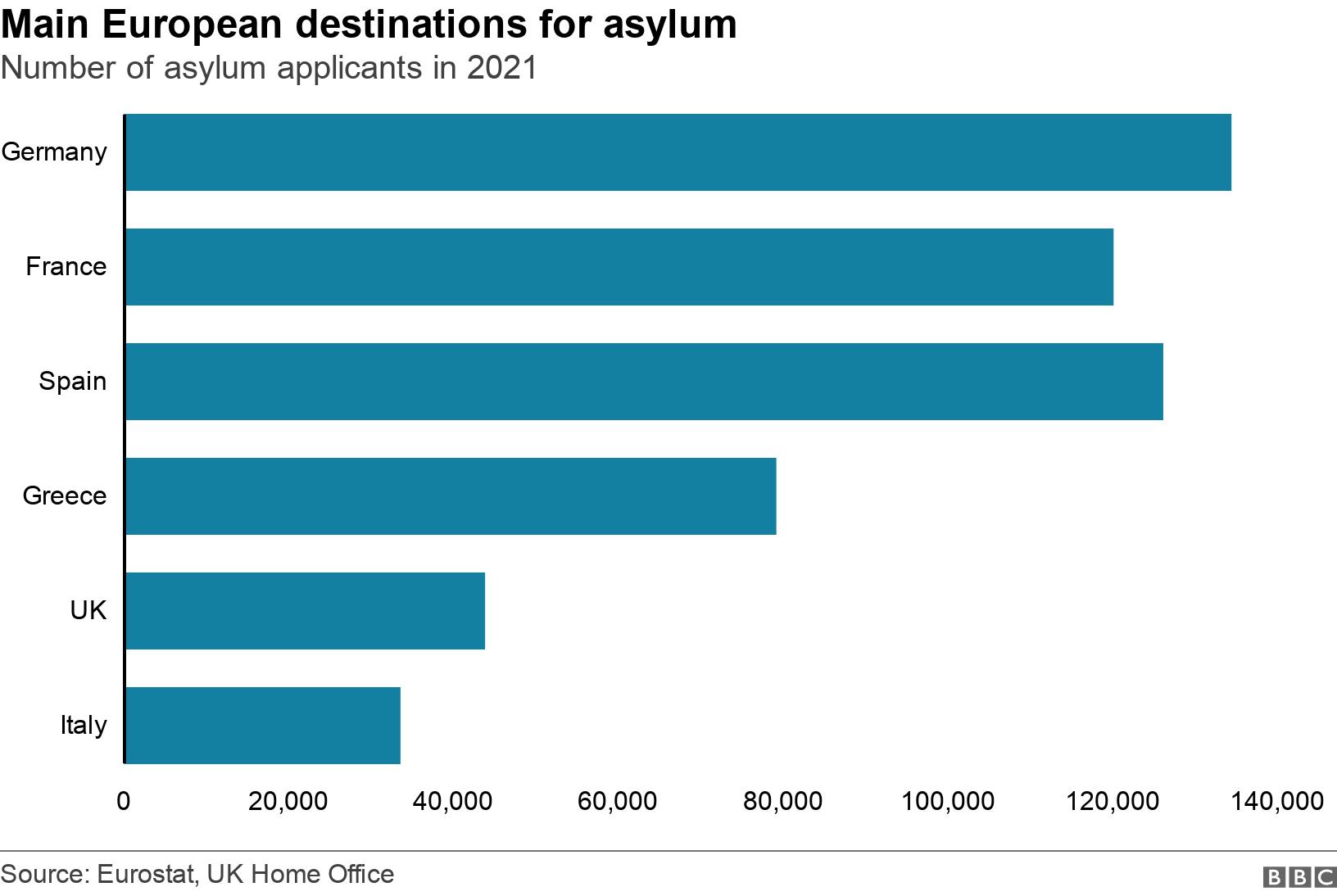

Many migrants already choose to make an asylum claim in the first country they arrive in – such as Greece, Turkey or Italy – and only a minority choose to travel on to the UK.

Last year, Germany had the highest number of asylum applicants in the EU (122,015 applicants), while France had 93,475 applicants.

In the same period the UK received the 5th largest number of applicants (36,041) when compared with countries in the EU (around 7% of the total). This represents the 17th largest intake when measured per head of population, according to UN Refugee Agency.