For nearly 20 years, she’d taken second place to a lead singer – first Diana Ross, then, in the 1970s, Jean Terrell.

Launching a solo career meant that, for the first time, she would be the centre of attention.

“I was used to singing ‘oohs’ and ‘babys’,” she said. “Now there are words. I had to learn all over again.”

But Wilson, who has died at the age of 76, was always more than a backing singer. She was the lynchpin of The Supremes, keeping the group intact and on the road after Ross’s departure.

She coached three new line-ups and cultivated their live audience in Europe – where, she realised, “you don’t have to have a current record or product to be remembered and loved and respected for your craft”.

The first of those songs, Where Did Our Love Go, was even beamed into space so that astronauts on the Gemini 5 mission could enjoy The Supremes’ glossy pop harmonies.

For three girls from the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects of Detroit, it was success on a scale they could never have imagined.

“Miracles do happen,” Wilson told Pure M Magazine. “It happened to us. We worked hard for it, but [we] totally, totally enjoyed being on top.

“We travelled the world, we met all kinds of people, worked with all kinds of people, it was one of those great experiences. Maybe everybody can’t handle it, but I certainly did, and I certainly enjoyed it.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESWilson was born in Greenville, Mississippi, on 6 March 1944. Her parents separated when she was young and she was raised by family members until she was 10 years old, believing for many years that her mother was actually her aunt.

The family moved to Chicago and later Detroit, where they attended Aretha Franklin’s father’s church every Sunday.

Wilson, who learned to sing by imitating Lena Horne records, formed her first group with Aretha’s sister, Carolyn, when she was in junior school.

The Supremes were the creation of a Detroit group called The Primes who wanted a new girl group to support them at local shows. They’d already found two singers, Betty McGlown and Florence Ballard – who suggested adding Wilson, her classmate, as a third member.

Wilson then recruited Diane Ross, who she’d first spotted from of the window of her apartment, calling her “the most energetic and pretty girl I’d ever seen”.

Diamonds in the rough

Christened The Primettes, the band started performing covers of songs by Ray Charles and The Drifters at social clubs and talent shows around Detroit.

“I recall when we first got together… I absolutely felt complete,” said Wilson in 2014. “I absolutely never had another thought of doing anything else in my life.”

They quickly won an audition from Motown founder Berry Gordy – but he refused to sign the band until they had graduated from school.

Determined not to be forgotten, they would hang out on the lawn outside the label’s headquarters until, one day, a producer came out and told the teenagers he needed someone to perform hand claps on a record.

“We jumped and said, ‘We’ll do it,'” Wilson told The Wall Street Journal last year. “Berry Gordy said, ‘Wow, you girls are serious.’ He signed us.” (In fact, the girls’ parents had to sign the contracts as they were still underage).

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESThe band were quickly renamed The Supremes (other options included The Melodees, The Jewelettes and The Sweet Ps) and put through the “finishing school” by Maxine Powell, the Miss Manners of Motown.

“She used to tell us, ‘You girls are just diamonds in the rough and we are here to polish you’,” Wilson said.

“At the age of 15, Mrs Powell taught us to keep our knees together, how to get in and out of a car and she also said something that we used to laugh at: ‘Never let your buttocks protrude.'”

Primed and polished the band nonetheless suffered a series of flops at the start of their career. In Motown’s offices, they became known as “the no-hit Supremes”.

McGlown left the band in 1960 and was replaced by Barbara Martin, who then left in 1962.

“We were still learning our trade,” Wilson told the BBC in 2014. “I think after a couple of years, Berry Gordy recognised we were getting more serious about our careers – it wasn’t just a little hobby any more.

“So he put us with his best writing team – Eddie and Brian Holland and Lamont Dozier. And 1964 was the year it suddenly all happened for us.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTPA MEDIA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTPA MEDIATheir first number one was Where Did Our Love Go, recorded as a trio in 1964.

Holland-Dozier-Holland had originally written it for Wilson, thinking it suited her grittier soul voice, but Gordy insisted Ross – who by this stage had changed her name to Diana – should take the lead vocal.

That set the pattern for the band’s next four number ones – Baby Love, Come See About Me, Stop! In The Name Of Love and Back In My Arms Again – where Ross was consistently thrust into the limelight.

Even after the band’s demise, she curated The Supremes’ legacy, staging exhibitions of their gowns and writing two best-selling books documenting their achievements.

In their 1960s heyday, the Motown group rivalled the Beatles for commercial success – at one point scoring five consecutive number one singles in the US, an achievement that’s still unmatched by any other female vocal group.

By 1967, Gordy, who was romantically involved with the singer, had renamed the band Diana Ross & The Supremes. But Wilson never bore a grudge against the star.

Diana’s ambition was “her strong point,” she told Outsmart magazine in 1986. “She was not like me – she did not wait for things to happen; she went out there and made things happen. I admired that in her.”

Role models

As the hits continued to rack up, The Supremes were a constant presence on radio and television – subtly contributing to shifting perceptions of race in America.

“TV really helped us,” Wilson later recalled. “People were able to see us all over America and see black people in a different light. We were human beings. We were respected. We were loved.”

The band’s glamorous style was also a political statement – projecting black affluence and sophistication in the middle of the Civil Rights era.

“We were role models,” Wilson said. “What we wore mattered.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTPA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTPAThe Supremes “were three of the most beautiful women I had ever seen,” wrote Whoopi Goldberg in the foreword to Wilson’s book, Supreme Style.

“These were brown women as they had never, ever been seen before on national television.”

Seeing them perform, Goldberg was encouraged to think that “I too could be well-spoken, tall, majestic, an emissary of black folks” who, like the band themselves, “came from the projects”.

The band’s songs also tackled some of the big social taboos of the day – with Love Child and I’m Living In Shame addressing the stigma around single mothers and illegitimate children.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESIn 1966, the album Supremes A’ Go-Go became the first record by an all-woman group to top the US album charts, knocking the Beatles’ Revolver off the number one spot.

But by this stage, Ballard, who had been sexually assaulted as a child, was spiralling into depression and alcoholism. She was removed from the group in 1967 and replaced by Cindy Birdsong. She later died of a heart attack, aged 32.

Ross left the group soon after to pursue a (wildly successful) solo career, leaving Wilson as the only original member still in the act,

“I made up my mind that I didn’t want my dream to die,” she told the Chicago Tribune in 1986. “Everyone else was giving up the ship, so to speak. I was the ship… I was The Supremes.”

With Jean Terrell on lead vocals, the band scored hits in the early 1970s with songs like Stoned Love and Nathan Jones, but they never really recovered from losing Ross.

Wilson laid the blame with Motown, feeling it had failed to promote or support the group’s new line-up; and she later sued the label over the rights to The Supremes’ name, and the terms of her contract as a solo artist.

“Motown didn’t give me what I thought I should get in the contract,” she explained. “They treated me like I was a newcomer, not someone who had helped build the company.”

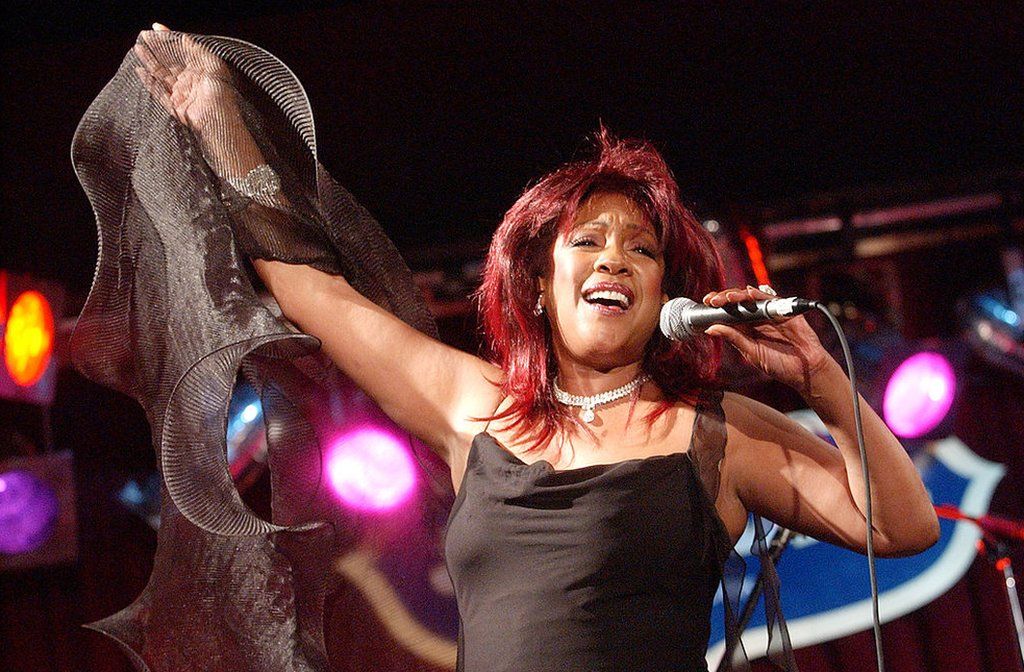

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESAs the band faltered, Wilson’s private life was causing even greater pain. She had married Pedro Ferrer in 1974, calling him “a charismatic man who could handle any problem”, but the relationship quickly turned sour.

“He was a handsome devil with a gorgeous Afro – dashing, charming and seductive,” she wrote in her book, Supreme Faith. “At first he gave me confidence, made me see that I had so much to offer without Diana. But I also found out Pedro had a violent temper.”

Exploding into jealous rages, Ferrer “beat my face, gave me black eyes” and slashed her face with a glass, nearly severing her ear.

In 1979, she gave him a year to clean up his act. When he didn’t, she walked away and their divorce became final in 1981.

The couple had three children, the youngest of whom, Rafael, died in 1994, when Wilson’s jeep hit the central reservation of a Los Angeles freeway and overturned.

She later said it was her faith in God that helped her come to terms with the trauma.

“Physically I have healed. Emotionally it’s ongoing,” she told The Chicago Tribune. “[But] I was probably as strong the first day as I am now because of my belief.

“We’re never taught about how to handle death. Death to me is a wonderful part of the living experience, so when my son passed I pretty much understood and said goodbye at that time. I cry every day, but then I get right back and do what I have to do.”

Legal campaigns

Wilson found major success in the 1980s with her memoir, Dreamgirl: My Life as a Supreme. The title was taken from the Broadway musical Dreamgirls, which was based on The Supremes’ career (Wilson called the play “dead on”) and the book scrupulously detailed the abuses the band had suffered at the hands of the record industry.

The Supremes were tied to a 3 per cent royalty rate (less expenses), she revealed, meaning they would have made less than $5,000 (£3,629) from a record that sold a million copies.

A New York Times bestseller, it remains one of the most popular rock-and-roll autobiographies of all time. Wilson followed it up with a second volume, and a book on The Supremes’ style.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESIn 2001, she received an associate’s degree in arts from New York University, the result of five years studying in between touring commitments.

“My mother couldn’t read or write, and the one thing she always stressed was education,” she said as she donned her graduation robes. “It’s a personal achievement and I’m very proud of myself.”

In her later years, she also appeared in musicals, became an inspirational speaker and appeared in the 2019 series of Dancing With The Stars – despite having heart bypass surgery in 2006.

Fiercely protective of The Supremes’ legacy, she also lobbied – successfully – for copyright laws that made it illegal for tribute acts to pass themselves off as the real thing.

And she remained proud of her achievements until the very end.

“The music has lasted, it’s still fresh,” she said in 2019. “Motown music still has a current sound to it, which is really wonderful. And it’s great to be a part of it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.