In south Johannesburg, the streets are full of people on the move at Christmas time.

Some residents seize the opportunity to leave this great, sprawling city for second homes and small family plots in rural South Africa.

Others empty their pockets in preparation for a few days at home in the irrepressible townships of Soweto, Alexandra and Lenasia.

The blur and whizz of holiday-related motion is something of a tradition and it has been replicated in neighbourhoods like Dobsonville for years.

Down on Tati Street, there is an old soldier who came home at Christmas, 75 years ago, and as we walked past his tidy-looking home, we could hear him singing from the front porch.

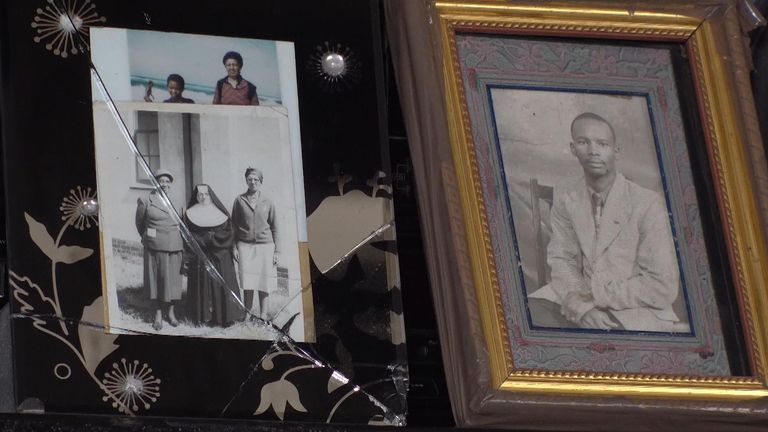

His name is Simon Mhlanga, one of a tiny number of surviving members of South Africa’s Native Military Corps, and we asked him if he would tell us a little bit about his life.

“At your service,” he said, offering me a crisp salute and a personal tale that is also a story of South Africa, both past and present.

I asked him about his age.

“I am about 106,” he said, but a number of his relatives, who were sitting nearby, shouted “111”.

Official documents say Simon is 101 but his daughter Clara says government officials in the colonial era used to guess how old black people were – and they got her father’s age wrong.

Mr Mhlanga grew up in a town called Roodepoort and life was clearly harsh. He signed up for the military in 1941 because he thought it would be better to die in the army than waste away from hunger at home.

“I went to the army because of my poverty… it was the only other way (to) die… so then I left my parents and went away and I didn’t even tell them I was going to the army.”

Encouraged to go to war by the country’s leaders, who were chronically short of recruits, approximately 80,000 black South Africans volunteered for the Native Military Corps. However, they were not allowed to serve as equals with white soldiers on the front line.

Instead, they worked as guards, labourers, stretcher bearers and medical aides – and many served with great distinction.

Mr Mhlanga guarded prisoners of war in Italy and Germany and returned to South Africa as a non-commissioned officer. But he didn’t get much in the way of thanks from the authorities. White soldiers were given new homes – blacks got boots or bicycles.

“I was given bicycle, yes, then I had that bicycle of mine.”

“How did you feel about it?” I asked.

“To me it was, you know, I had to accept it but really I felt cheated by the government of South Africa to give me a bicycle.”

For many of his fellow servicemen, the injustices continued into death.

War grave cemeteries in South Africa were strictly segregated. Government rules meant blacks were not allowed to share the same plots as whites and some members of the so-called “native regiments” have never been commemorated at all.

When a retired historian called Terry Cawood stumbled on four battered-looking books in South Africa’s military archive, he found the names of more than 1,000 black servicemen from the Native Labour Corps, a precursor to the Native Military Corps, who served Britain in East Africa during the First World War.

The names of regiment members had been written haphazardly on slips of paper and many were given inaccurate names like “Black Boy” or “Clan Boy” by superior officers who were either unwilling – or unable – to record their details properly.

“The documentation was very rudimentary, not a lot of effort was put in – a lot of them are written in pencil and over the intervening years they have faded… obviously the servicemen had tribal names but that’s been lost and there was no registration of births at the time.”

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which commemorates 1.7 million soldiers who died during the First and Second World Wars, has decided to tackle the issue of unrecognised and non-commemorated military personnel by forming a special committee which will make recommendations in March.

Panel members carry a great responsibility to consider and address past wrongs. In East Africa, the colonial authorities decided not to commemorate by name the thousands – or possibly hundreds of thousands – of men and women who served the British as porters and labourers during the First World War. We do not know how many died and there are no known burial grounds.

Back on Tati Ave, Simon Mhlanga told us he does not worry too much about the army anymore.

When he left it, he took up singing and dancing and he coached marching bands and “drum majorettes” in competitions across South Africa.

It was clear that the experience has provided him with many years of joy. We left his home as we entered it – to the sound of joyous song.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.