Faced with a lack of government and community support, stigma and abuse, many children with disabilities in Uganda are hidden indoors, with few options for specialized care. But now community leaders are working to change this, through education and services for families in need.

The corrugated iron door unlocks from the outside and pushes open slowly. A girl in a faded dress and green sandals looks up as the unforgiving African sun pierces the room. She does not move. Sitting on a wooden chair, she is tethered by a length of thin cloth, fastened tight around her wrist.

The corrugated iron door unlocks from the outside and pushes open slowly. A girl in a faded dress and green sandals looks up as the unforgiving African sun pierces the room. She does not move. Sitting on a wooden chair, she is tethered by a length of thin cloth, fastened tight around her wrist.

Twelve-year-old Catherine Asinge is bound daily to a chair in a storehouse with chickens and sacks of cassava

Catherine is 12 years old. Small for her age, she looks even younger sitting in the dark, hands resting in her lap. For more than half her life she has been locked inside this hut, no bigger than a garden shed. She sleeps on the concrete floor without a mattress, between sacks of dried cassava. Chickens with which she shares the storeroom roost in baskets.

“This should not be a normal thing,” sighs Fred Alimet, a pastor in this swathe of countryside in Soroti District, in Uganda’s east, where farmers live with their families in mud-brick huts built on terracotta dirt. “But because this child has a disability she is being hidden.”

Pastor Fred wipes the sweat from his forehead and kneels down to loosen the cloth around Catherine’s arm. She recoils, so he calls in her mother. Not a word is spoken as she unties the tether, and Catherine stands and walks outside into the early afternoon.

The girl’s mother, Sarah Akello, does not live here. Akello’s husband rejected Catherine because she has a disability, believing her to be cursed or another man’s child. “The father doesn’t want to see her,” says Pastor Fred, translating Akello’s words. “The father is asking the mother how she got this child. The other seven children are OK but this one is having a problem.”

Catherine Asinge stares out from the hut where she remains tethered

Akello lives with her husband, but walks the three-kilometre bush tracks from her home to sit outside the hut where her youngest child has been hidden since she was five. Akello explains that Catherine is locked away here, on her oldest son’s plot of land, because of what will happen to her if she wanders off. Like many children in Uganda, Catherine has never been diagnosed with a specific condition, but she is disabled – and that makes her a target.

“Sometimes when she leaves here she gets beaten from outside, she gets abused,” Akello says. “She has been beaten many times.” Standing three feet away, absently present, nobody speaks to Catherine. When the caseworkers leave she is returned to the hut, the piece of cloth with small blue flowers tied back around her wrist.

When not leading his congregation in Soroti, eastern Uganda, Pastor Fred Alimet travels to other areas to educate communities about children with disabilities

Here, people with physical or intellectual disabilities are often considered a burden; unable to work, or to learn. Stigma is fuelled by beliefs that people with disabilities are cursed. Some believe disability is caused by sin; a promiscuous mother or the wrongdoing of ancestors. Some believe disabled people are possessed. Some believe they are not human at all. Disabled children rank among the most socially outcast and vulnerable in Uganda. They are more likely to be denied healthcare, less likely to go to school, at higher risk of abuse and sexual violence. Across the country, these children are hidden away, warehoused out of sight, or worse.

Al Jazeera visited Uganda earlier this year to meet dozens of disabled children and document the experiences of some of the families that try to care for them. Their stories share the thread of social exclusion, their struggle exacerbated by extreme poverty.

Outside the village storehouse, Pastor Fred Alimet speaks to Catherine’s mother, Sarah Akkello

The corrugated iron door unlocks from the outside and pushes open slowly. A girl in a faded dress and green sandals looks up as the unforgiving African sun pierces the room. She does not move. Sitting on a wooden chair, she is tethered by a length of thin cloth, fastened tight around her wrist.

Catherine is 12 years old. Small for her age, she looks even younger sitting in the dark, hands resting in her lap. For more than half her life she has been locked inside this hut, no bigger than a garden shed. She sleeps on the concrete floor without a mattress, between sacks of dried cassava. Chickens with which she shares the storeroom roost in baskets.

“This should not be a normal thing,” sighs Fred Alimet, a pastor in this swathe of countryside in Soroti District, in Uganda’s east, where farmers live with their families in mud-brick huts built on terracotta dirt. “But because this child has a disability she is being hidden.”

Pastor Fred wipes the sweat from his forehead and kneels down to loosen the cloth around Catherine’s arm. She recoils, so he calls in her mother. Not a word is spoken as she unties the tether, and Catherine stands and walks outside into the early afternoon.

The girl’s mother, Sarah Akello, does not live here. Akello’s husband rejected Catherine because she has a disability, believing her to be cursed or another man’s child. “The father doesn’t want to see her,” says Pastor Fred, translating Akello’s words. “The father is asking the mother how she got this child. The other seven children are OK but this one is having a problem.”

Akello lives with her husband, but walks the three-kilometre bush tracks from her home to sit outside the hut where her youngest child has been hidden since she was five. Akello explains that Catherine is locked away here, on her oldest son’s plot of land, because of what will happen to her if she wanders off. Like many children in Uganda, Catherine has never been diagnosed with a specific condition, but she is disabled – and that makes her a target.

“Sometimes when she leaves here she gets beaten from outside, she gets abused,” Akello says. “She has been beaten many times.” Standing three feet away, absently present, nobody speaks to Catherine. When the caseworkers leave she is returned to the hut, the piece of cloth with small blue flowers tied back around her wrist.

Here, people with physical or intellectual disabilities are often considered a burden; unable to work, or to learn. Stigma is fuelled by beliefs that people with disabilities are cursed. Some believe disability is caused by sin; a promiscuous mother or the wrongdoing of ancestors. Some believe disabled people are possessed. Some believe they are not human at all. Disabled children rank among the most socially outcast and vulnerable in Uganda. They are more likely to be denied healthcare, less likely to go to school, at higher risk of abuse and sexual violence. Across the country, these children are hidden away, warehoused out of sight, or worse.

Al Jazeera visited Uganda earlier this year to meet dozens of disabled children and document the experiences of some of the families that try to care for them. Their stories share the thread of social exclusion, their struggle exacerbated by extreme poverty.

‘Just waiting for this child to die’

“There has been a lot of resistance towards these children over the years,” says Stephen Kabenge from Embrace Kulture, a not-for-profit that works to find hidden children. “So many organisations are trying to fight it, but it is not one man’s struggle.” Embrace Kulture houses and schools 20 disabled children and young adults at its headquarters in Entebbe, a gated oasis about an hour’s drive southwest of the Ugandan capital of Kampala. It wants to grow this number tenfold, an ambitious goal even before coronavirus wound back efforts to help some of the estimated 2.5 million children living with disability.

“There has been a lot of resistance towards these children over the years,” says Stephen Kabenge from Embrace Kulture, a not-for-profit that works to find hidden children. “So many organisations are trying to fight it, but it is not one man’s struggle.” Embrace Kulture houses and schools 20 disabled children and young adults at its headquarters in Entebbe, a gated oasis about an hour’s drive southwest of the Ugandan capital of Kampala. It wants to grow this number tenfold, an ambitious goal even before coronavirus wound back efforts to help some of the estimated 2.5 million children living with disability.

Kabenge speaks a lot about what he calls the “transition to acceptance”. Put simply, it is a long road. It starts with navigating the patriarchal minefield of bloodlines and lineage. Then comes the battle against stigma. Intervention, Kabenge stresses, must start with education. “We can’t blame these parents,” he says. “If you have been told your whole life that disability is contagious or that these people are cursed, then it is going to take some time. There is no way we can change that in a month. But if the situation is critical our priority is always to preserve the life of the child.”

Nine-year-old Salma Kobusinge is held by her mother Nono Zubeda

Today, Kabenge is travelling across town to check in on a single mother and her daughter. Nearing the house, he sums up the plight of many parents, mostly women, struggling to care for disabled children alone. “She has told me she is just waiting for this child to die,” Kabenge says as the van comes to a stop.

The house is in Lugonjo, a densely populated slum near the edge of Lake Victoria. Outside, a neighbour, a bony middle-aged woman, is slumped against a wall gripping an almost-empty bottle of waragi, a local home-brewed liquor. The brick building has two small rooms. No bathroom or kitchen. Food is prepared outside, next to a hollowed-out car tyre filled with aluminum pots and plastic containers. Piles of laundry, which the mother earns a living washing, hang over the bed. A children’s alphabet chart is stuck to the wall across from a calendar that has not been changed since August 2018. There is one window, a single metal bar running down the middle.

The scars over her body tell the story. Salma is almost 10, but totters like she is still learning how to walk. She stumbles forward on unsteady legs, then backwards, always about to fall. Her mother, Zubeda Nono, steadies her with a hand under the armpit. Then Salma wrestles away again, jerking off the walls, or writhing on the chipped floor, or crawling on her hands and knees. Her eyes are vacant, unblinking.

When she needs water, Salma lies down next to a cup; when she is hungry she picks up a plate. She goes to the toilet where she stands. Nono looks at the worn plaster on the wall. “She always plays around that part with her head and mouth,” she says. “Sometimes she wants to be like a mad person.”

Salma lives with sickle-cell disease and epilepsy and is prone to fall.

Salma has sickle-cell disease and epilepsy. Health workers believe she also has autism but say this is not being treated because of a shortage of screening and diagnosis services. She is partially deaf, blind in the right eye, and cannot talk. Nono lays out her daughter’s medication and lists what each pill is for. “She has to take all this medicine until she dies,” Nono says. “If she doesn’t take it she will scream at the top of her voice.”

Nono fetches two thin, soiled mattresses and drops them on the floor to demonstrate how she softens Salma’s falls when she goes out. Using a large stone, Nono secures the lower half of the door shut from the outside, leaving the top part open so neighbours can peer in to check if the child has collapsed or had a seizure. The mother of four knows she should not leave Salma alone, but this was her routine when she went to work, five days a week, until her daughter was six.

“I’m doing a good job,” Nono says matter-of-factly, “because the child is still alive.”

‘We need an intervention’

On paper, Uganda is one of the success stories out of Africa. Rocketing economic growth means fewer people live below the poverty line. Child deaths are down. Immunisation rates are up. There is more clean drinking water than ever before, and people are living longer. But specialist medical services across the sub-Saharan African nation are in short supply. Uganda has a population of more than 40 million people and just one national-referral mental health facility, an overcrowded hospital in the capital where children are jammed in with adults. The void left by thinly spread disability services is filled by traditional healers, witch doctors and crooks. One witch doctor said he would only speak about how he cured disability in return for payment.

Advocates say reliable government data on disability rates in Uganda does not exist, not to mention support services. Michael Miiro, a disability rights advocate and consultant who used to work for the government, says the second major challenge is culture. “Many people, including the parents, haven’t accepted these children to the extent that they don’t see value in them, and they’re not giving [them] the basic needs like any other child,” he says. “This becomes a challenge because a child grows in a state of self-denial, with no support, with no love from the parents and the community.”

Goats are untethered during the day, allowing them to roam freely and feed

If disabled children are lucky enough to go to school, chances are that the resources needed to help them simply do not exist. “There’s no special arrangement or special grant that is set down to support these children,” says Miiro. “If they don’t have the money or the resources of information this child will stay as they are. They cannot access drugs. [They] depend on nongovernment organisations.”

The trickle of support that did exist has almost dried up. The coronavirus lockdown has thrown more hurdles in the path of survival for disabled children; transport and food have become more costly, life-saving drugs more difficult to access. Miiro and others say there has also been a spike in reports of sexual abuse during the pandemic. “They are really very much suffering during this period,” he says. “We need an intervention that can uplift that status of children with disability.”

The parents who kill their children

In the waiting room of a small health clinic outside of Kampala, two heavily pregnant women sit on white garden chairs under a poster advertising services to help with fertility, menstruation, and changing a child’s gender. They are waiting for traditional birth attendant Ruth Nakimera, a 71-year-old with cropped grey hair who wears colourful dresses with shoulder pads. Traditional maternity care was passed down to Nakimera by her grandmother, but she went on to complete formal training as a midwife. This type of healthcare is common in Uganda, where clinics such as these provide antenatal and postnatal care.

Nakimera ushers one of the women into the back room. The heavily pregnant 25-year-old lifts her top and lies on a crumpled, plastic-covered mattress. Nakimera checks the baby’s position with a gentle rocking manoeuvre. She presses her ear to the woman’s rounded abdomen, her version of a stethoscope, to hear the heartbeat. Then she turns her attention to the mother, pulling her lower eyelids down with her thumb to read her blood levels.

Ruth Nakimera, a traditional birth attendant, sits in the waiting room of her clinic; to her right are crates full of ingredients for her medicines

Nakimera has seen it all. Mothers have laboured on the floor of her waiting room. She remembers delivering babies with club foot. There have been others with Down’s syndrome and spina bifida, and recently, one with partially formed arms. Parents of older disabled children seek out the help of herbalists like Nakimera, believing them to be mad or bewitched. “Most times they show a lot of grief,” she says through a translator, “because by the time they run to me they are already worried that something is not going right with their baby.” Nakimera prescribes herbal medicine but says she always advises the parents to go to hospital, too.

When she encounters a baby with a disability or birth defect, Nakimera is careful. She never tells the mother too much, right away. “I have a past with that,” she says. Many years ago Nakimera’s grandmother delivered a baby with a cleft lip. After the birth, Nakimera says, her grandmother told the mother her child’s upper lip and nose were split. “The woman immediately told her, ‘I cannot raise such a baby, please end its life’.” That child was raised by Nakimera’s grandmother until the age of six. “Ever since then,” Nakimera says, “when I find something wrong, I will wait for some time and then deliver the news, and give ways for how the parents can help the baby.”

Ruth Nakimera closes the blinds for privacy before performing a routine check up on 25-year-old Haddijjah Nabweteme, who is eight months pregnant with her fourth child

Many people in Uganda told stories about so-called “mercy killings” – the practice where parents abandon their children in the bush or violently end their lives. Several parents recounted being told by family and friends to throw their disabled children into the communal pit toilet, or withhold medicine, or poison them. In 2018, the European Parliament passed a resolution condemning the ritual killing of children and newborns with disabilities in Uganda, and called on authorities to provide more support to families. But such is the shame and secrecy shrouding disability here, the incidence of the practice is impossible to measure.

Jimmy Aner is a quiet, dedicated village healthcare worker in the northern region of Uganda who supports parents of children with disabilities and works hard to dispel myths around witchcraft. He painfully recalls the scorching hot morning during one dry season when he was driving back to the city of Lira and watched a mother kill her toddler. He saw a woman dressed in black, a young child tied to her back, walk into a river from a clearing by the side of the road. When she reached the middle of the river, he says, the woman untied the black cloth wrapped around her, and let the small child fall.

So-called ‘mercy killings’ are an accepted part of life in some rural areas, as confirmed by community outreach worker Jimmy Aner

“The child fell into the water,” Aner says softly. “She dropped the child just near the road and continued moving. She was running into the bush. We stopped but … unfortunately I don’t know how to swim and I was fearing to dip myself into the water.”

Aner remembers the young girl’s naked, bloated body being pulled from the water downstream and taken to the local elders. “When the child was removed, we found out that the child had some disability,” he says. “The baby was lame and the head was swollen. The hands were very little and the two hands were deformed.

“It is difficult to see that. Sometimes I do not like to pass by that place, because when I reach that river I recall what happened.”

Two years ago, local journalist Gerald Bareebe reported that the killing of disabled children in rural Uganda was widespread. Bareebe took testimony from two mothers who described in devastating detail how they murdered their children. In both cases the fathers had abandoned the family and communities had turned on the mother and child. “It takes a village to raise a child,” Bareebe says in his report. “It seems it also takes a village to kill one.”

Survival

They came in the night. Armed with hammers and stones, the mob surrounded the small hut where the children slept. The girl didn’t have time to get her little brother out before the roof came crashing in. She escaped without physical injury; he was dragged from the rubble later, alive but covered in blood.

“After they finished banging the house I saw my aunties and the men outside,” recalls Harmony. “Then they just went away.” The young girl said she cradled her brother, Ezra, while he cried and they waited at the ruins of their house for their parents to come home.

Ezra’s mother, Agnes Nangobi, runs her fingers across the jagged scars on her son’s forehead. “This is from the structure that fell on him,” she says. “From the blocks.” The mother of five used the blocks to rebuild their home by hand, but lives in fear that this house will also be razed. “They want us off this land,” Nangobi says. By “they”, she means her husband’s family.

“They say that I produce snakes, not children.”

Ezra was a healthy child until the age of four, when he developed problems speaking, walking and eating. Nangobi and her husband had seen it before; their oldest child’s health deteriorated at the same age. “The doctor said my daughter had spastic diplegia,” says Nangobi. “Then I produced this child. He had the same problem so I did not take him to anyone.” Their daughter died before her 10th birthday. Ezra is seven.

Around the same time that Ezra began experiencing health problems, his father, an electrician, was forced to stop work after suffering a stroke. They say that is when problems with his side of the family began. The father says they are being driven from their home because he is crippled and because they have had two children with disabilities.

Agnes Nangobi holds her seven-year-old son, Ezra Moro

It is not just their relatives who want them gone, Nangobi says. She lists several attacks from neighbours over the past year: crops ripped out of the ground, stones hurled at the house, and human faeces left at their door. “They tell us to go to another place, but we have nowhere to take the children,” she says. “Life is not easy since we have this.”

It is clear that Ezra is wasting away. He communicates only in groans. He cannot sit up on his own anymore, so Harmony spoon-feeds her brother on the floor, lifting his head for every mouthful. Looking on, Nangobi exhibits all the hallmarks of a mother in terror and despair. A woman unable to save her child. The only lesson learned since the loss of her daughter is that Ezra shares the same fate. Nangobi, her eyes perpetually filled with tears, says her son’s condition is worsening. She expects he will die soon.

‘I didn’t have anywhere to go’

Uganda has passed a series of laws and signed international treaties designed to protect the disabled, including becoming one of the first countries to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. But these public declarations chalk up to almost nothing in the lives of the parents fighting to keep their children alive, the children who know only being locked away, and the workers committed to helping them. While there has been some progress in access to education and healthcare, many disabled people continue to live on the abyss, with report after report drawing the same conclusions. The rights and needs of disabled people are “often ignored”, said one by the union representing disability groups. They are particularly at risk of “multiple forms of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation”, said another, by the United Nations Children’s Fund. A 2016 United Nations report, produced almost a decade after Uganda signed the disability convention, described in one sentence the positive measures the government had taken to promote the rights of disabled people, then detailed in 14 pages more than 50 concerns.

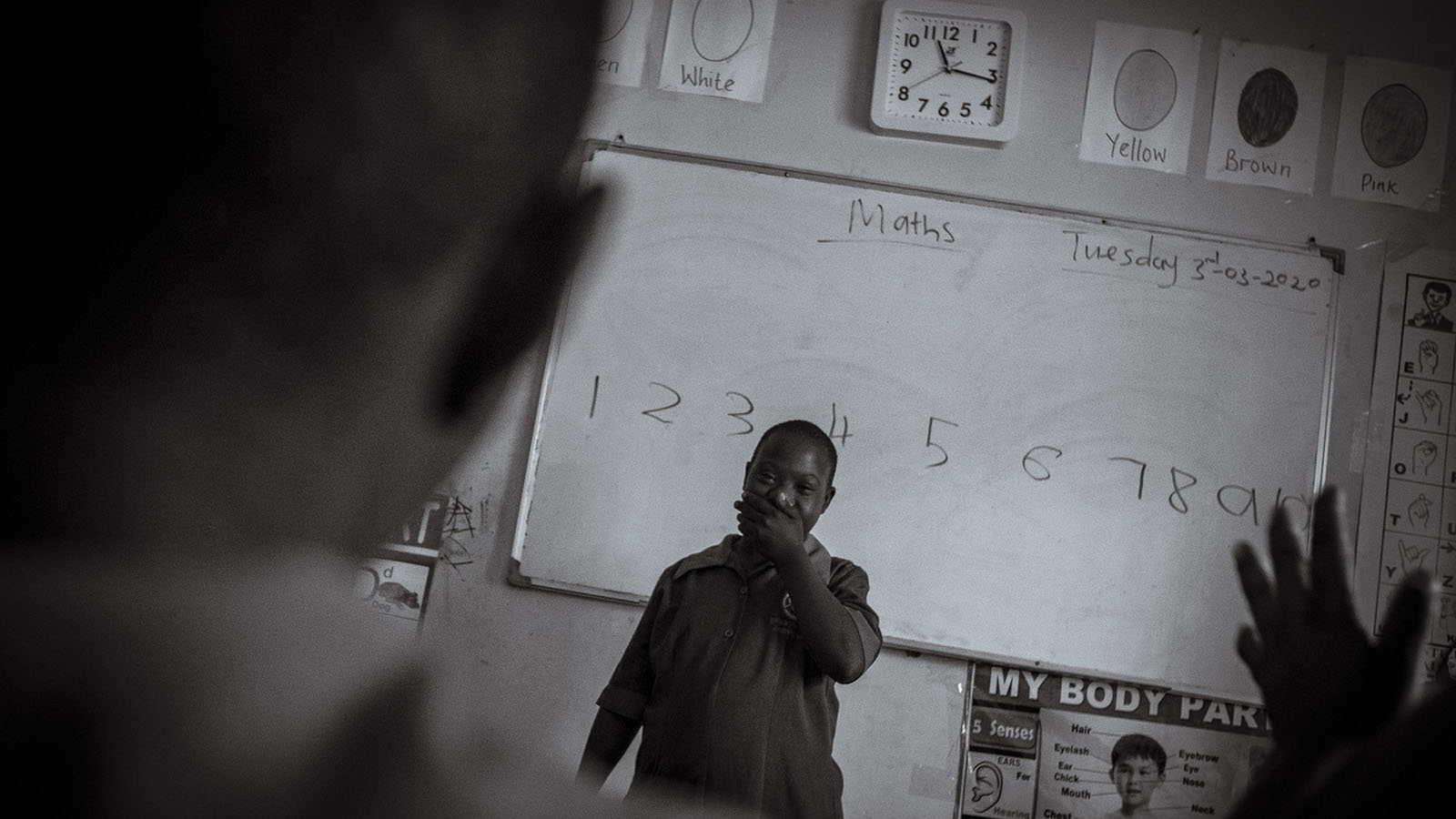

It is a cycle that the staff at Embrace Kulture are all too familiar with. The histories of the children at their centre are among some of the most harrowing: a girl with Down’s syndrome who suffered horrific sexual abuse; a boy whose ankles are scarred from years of being shackled with chains; a boy with autism who spent his days tethered to a tree. One report detailed the case of a disabled child who was locked in a cage. Embrace Kulture’s mission is deceptively simple: “No more hidden children.” It works to restore the basic human rights of children extricated from hiding, and to give them a chance at becoming independent adults. The children go to school, receive therapeutic support, and are given vocational training in areas like business, bakery and agriculture.

Students at the Aamanyi Centre, which is run by the NGO Embrace Kulture, prepare a plot for planting during their agriculture class

The students are grouped into two classes: Giraffes and Lions. In the Lions Room, Noeline Namata, a classroom aide, teaches the younger children about money. She holds up a banknote at the front of the class. “This is 2,000?” She stops. “This is 2,000,” repeats Namata, emphasising the question. “Shillings,” the children chorus back to her. “Next is what?” asks Namata. “From 2,000 we go to? From 2,000 we go to?”

“5,000,” shouts a boy huddled near the front. “Yes, which colour is it?” Namata points to the coloured A4 sheets of paper stuck to the wall above the whiteboard. “Green!” the children shout back. “Green, yes! From 5,000 we go to?”

One boy has been running in and out of the classroom, breathing heavily and strumming some wire clasped between his teeth with his hand. He is restless but eventually takes his seat against the back wall between two students, his hands linked behind his head, forearms pressed against his ears, rocking back and forth.

“From 5,000 we go to?” Namata continues. “10,000!” the children shout. “Yes! This is 10,000. This is 10,000.” The students work their way up to 50,000 shillings, then Namata goes around the room. “If I give you money, what can you buy?” The children take turns answering – chapati bread, chicken, apple, a dress, biscuit, onion, eggs – before each receives a riotous round of applause.

Ketty Akello fronts her class during a maths lesson at the Aamanyi Centre

Ketty is in this class. She is a beaming teenager who loves to dance. Her mother, Rose Akello, was kicked out of the house by her husband after she refused his demand to dump Ketty in the latrine. “He denied her completely. He refused her,” explains Akello. “He always said to me, ‘I don’t want that child in the home’. My husband chased me from home and doesn’t want me with the child. The community rejected me, they sent me away. They said they have never seen that type of child. Even my own parents refused me. I didn’t have anywhere to go.”

Akello says she moved from place to place with Ketty, who has Down’s syndrome, but always encountered the same problem. She pleaded for help, begged for mercy. Sometimes she tried to hide her daughter from the sneers and the scowls. Nothing worked. “People were saying to me to take the child to the witch doctor, throw that child, kill that child,” she says. “I became tired looking for help.” Then one day a few years ago, Akello found Pastor Fred, which eventually led her to Embrace Kulture.

It is through Ketty’s intervention that Embrace Kulture and Pastor Fred have been able to make inroads in the eastern district of Uganda, where Catherine was discovered tethered to a chair in the hut. During that visit, word quickly spread that an outreach team was in the area. When Pastor Fred and Kabenge’s team returned to their van in the afternoon, a group of parents and children were waiting.

Rose Akello, mother of Ketty Akello, dances with joy, signaling the arrival of Pastor Fred Alimet and community health outreach workers

They sit under a buttress tree on ripped blue and grey tarps. The mothers wear hopeless expressions. Children lie across their laps, or sit quietly in front of them. The younger ones breastfeed. Patiently, the mothers take turns asking for answers. They want to know why their children cannot sit or stand or swallow. Why they are incontinent or suffer from seizures. Can these children be educated? There is a blind girl and a little boy with twisted limbs. A child with a sinister-looking growth on her back. A suspected case of hydrocephalus. Children with Down’s syndrome and cerebral palsy.

A father – the only father who has travelled to be here – asks how he can feed his son, a frail seven-year-old he cradles in his arms like a newborn. The tormented man says his son’s condition has deteriorated to the point where he can only eat porridge, and even that is a struggle. At one point, an exhausted-looking mother near the front hands up her child’s medical records, a 96-page exercise book. The last entry from the hospital, a week earlier, says her seven-month-old suffers from a weak spinal cord and struggles to breathe. “Come back for future investigation,” the handwritten doctor’s note says.

Paul Oribo lives with cerebral palsy; his father, Simon Okurut has cared for Paul alone since his wife fled their village after Paul’s diagnoses

Kabenge emphasises that they are not here to offer false hope, just to try, maybe, to help a little. The advice is basic but practical: how to prepare food for children with feeding difficulties; how to build supports to encourage walking; and, too often, that the child needs to be taken to the hospital.

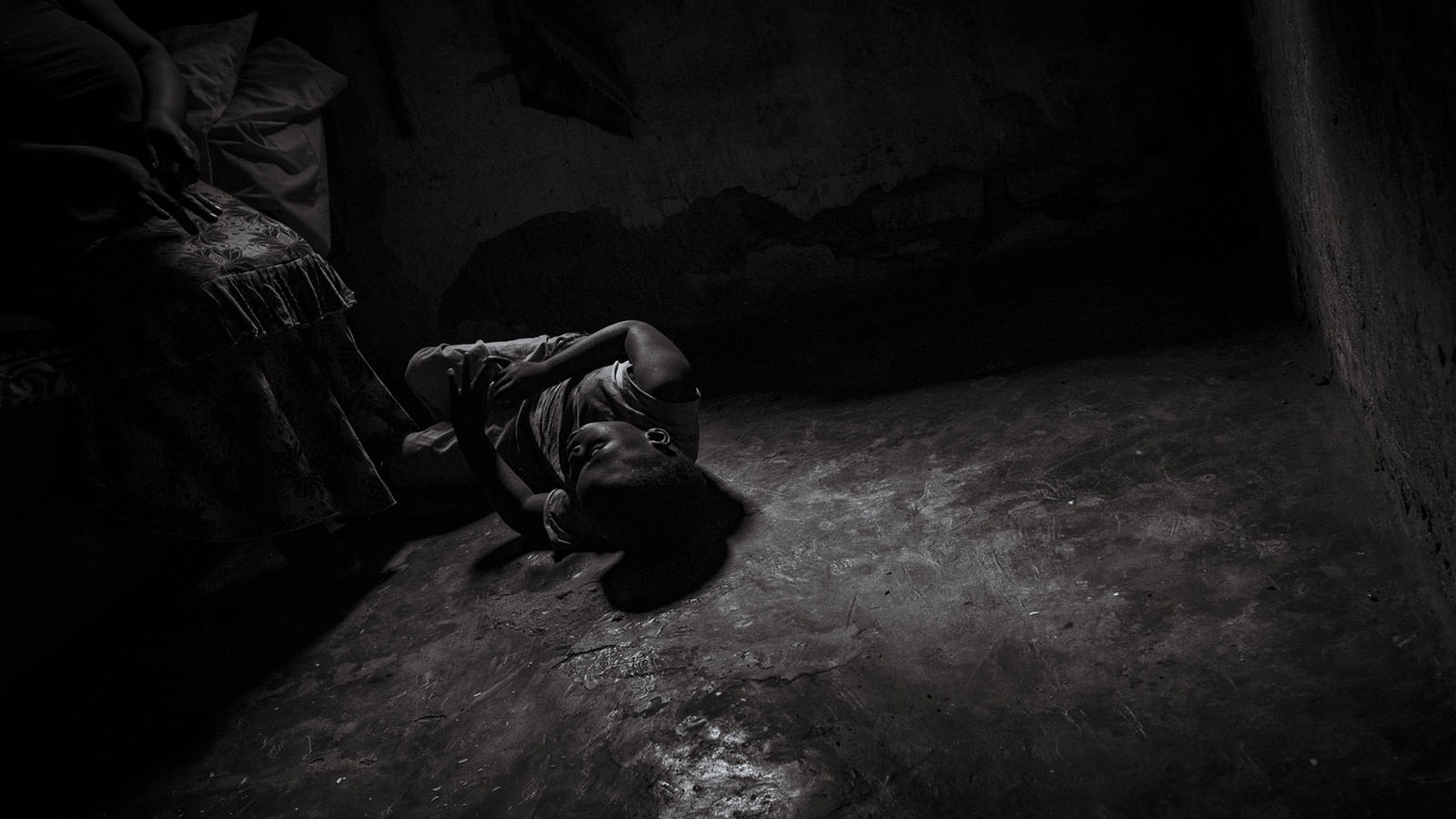

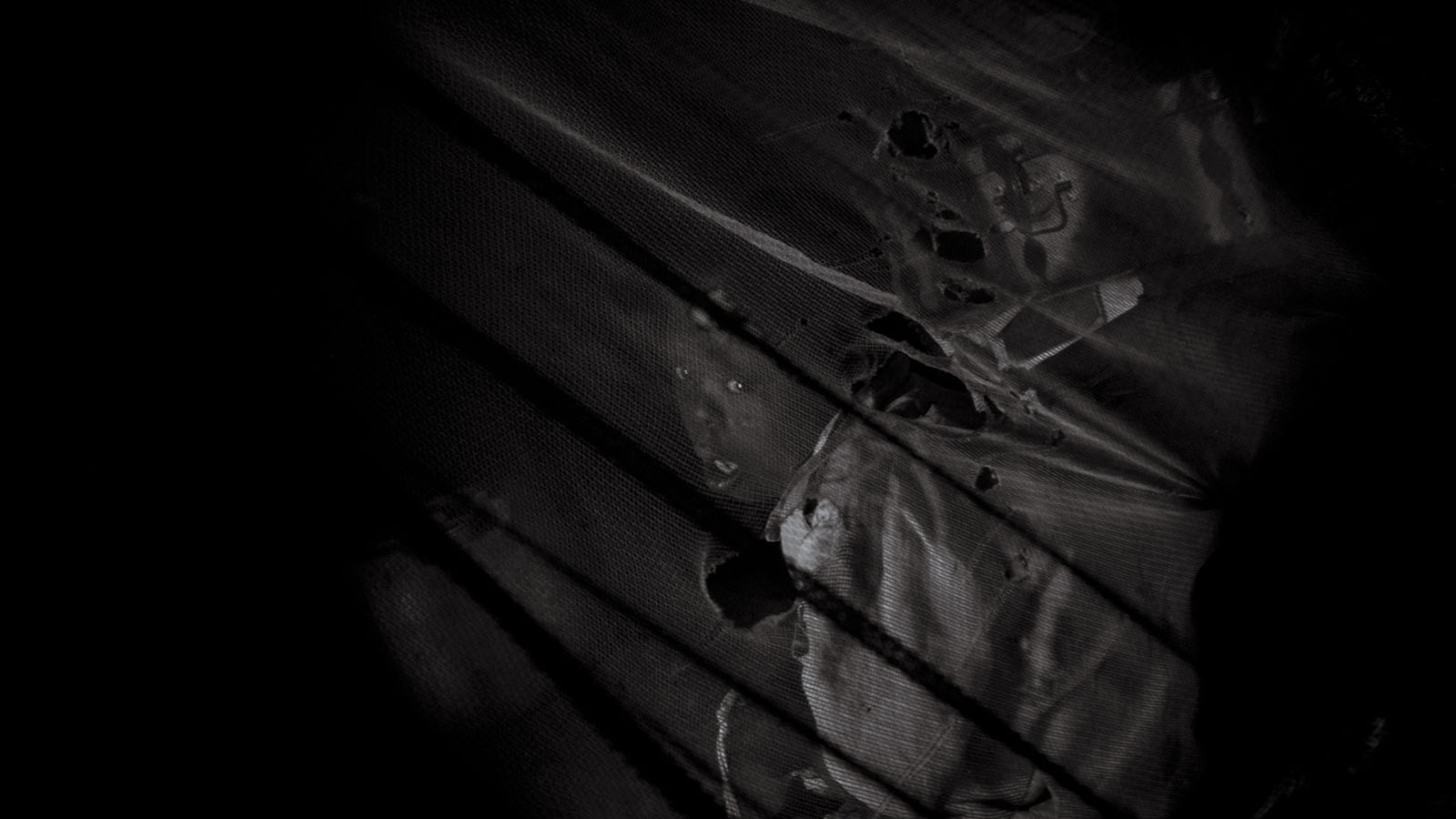

No more than 10 minutes’ walk from this spot, through wild mint and long dry grass, disability workers found another boy. Silas is locked inside a thatched-roof hut, tethered to a heavy log by rope and ripped cloth. A mosquito net with fist-sized holes hangs over a thin piece of discoloured foam on the floor. He has one toy, a ball made from tightly woven plastic bags. The door is tied shut from the outside, where the world goes on without him.

Silas’s parents are still together, a rare occurrence that health workers credit for the boy’s overall satisfactory health. His mother, Betty Ilolu, who had seven children before him, knew something was different when he was born. “I was asking what is this? What am I producing? Is this a human being? I thought God has given me a different thing, not a child,” she recalls.

“Each time when the child was growing he was so sickly. I was only waiting for the child to die, but the child did not die. When Silas got so sick I took him to the [health] clinic and they could not help. They said to take him to the hospital. When we went there they said his heart has a hole, only one part of the heart is functioning. They told me they could not help. They gave some painkillers and said to take him back home.”

In the past, 13-year-old Silus Odii has been assaulted and abused by neighbouring villagers because of his disability, so his parents Joram Odii and Betty Ilolu now tether him inside for his own safety

Silas’s father, Richard Okodel, says most people in their community told them to take him to the witch doctor, but as Christians they never considered this an option. “At times Silas would get so sick some people would say to just kill him instead of being disturbed day in, day out, by a child who will not get better,” Okodel says.

Asked if they had ever received any support from family, neighbours, community or the government, Ilolu slowly shakes her head. “Nobody,” she says. It was only earlier this year that Ilolu and Okodel learned there was a name for their 10-year-old son’s mysterious condition: Down’s syndrome.

Okodel says they started tying Silas up and locking him in the hut when he finally started walking, at the age of five, because neighbours, both adults and children, beat him bloody. Silas tried school last year but the same thing happened. On his first day he was singled out by classmates and teachers. “Children would gather around him and some would beat him or scare him,” his father says. “The teachers would not be patient. Sometimes they would beat him or push the child out of the class.”

Pastor Fred Alimet embraces Silus Odii after untying his tether

Pastor Fred says grassroots education is crucial to combating the child disability crisis “to teach them about the rights of these children.” He says, “Most people look for equality, but in Uganda it’s more about survival.” In this region alone, Pastor Fred says, there are at least 300 other children hidden away. “Most of these children are on ropes or chains. When I find it like this I don’t like it.”

The pastor asks Silas how often he is tied up. “He says a long time. He says, ‘I’m always here’.” He unties the tether from Silas’s wrist and lets it drop to the floor. Then he smiles at the little boy and takes his hand. “I am telling him he is handsome, he is good, he is not supposed to be tied like that.”

What did he say? “He says, ‘Thank you’.”

Silus Odii untangles the rope that is used to tether him to a crate

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.